Netlify’s platform team is responsible for building and scaling the systems designed to keep Netlify, and the hundreds of thousands of sites that use it, up and running. We take that responsibility seriously, so we’re constantly looking for potential points of failure in our system and working to remove them. Most of our platform is cloud agnostic, and since we favor an approach that minimizes risk, we wanted to extend that to include our origin services. This led to a project that culminated in us migrating our origin services between cloud providers on a recent Sunday night — without any service interruptions.

When you deploy a website to Netlify, your content automatically gets pushed to the edge nodes in our Content Delivery Network (CDN). If you make changes in your Git repository, your content is continuously and automatically synced with our origin servers and pushed to the CDN.

Our CDN runs on six different cloud providers, but up until recently, our origin servers relied on only one. That meant our origin servers were subject to the performance and uptime characteristics of a single provider. We wanted to make sure that in the face of a major outage from an underlying provider, anywhere in our network, Netlify’s service would continue with minimal interruption. Our origin services can now swap between three providers: Google Cloud (GCP), AWS, and Rackspace Cloud without downtime. This post will cover how we planned, tested, and executed our first multi-cloud migration

Planning for change

The main goal for this project was to have a multi-cloud production system where we could direct traffic to different providers on demand, without interruptions. Our primary sources of data are the database and the cloud store — the first for keeping references to the data and the second for the data itself. To keep latency down, we needed to run a production-ready copy of both sources in every provider. They also needed to have automatic fallbacks configured to the other clouds. For example, Google instances prioritize Google Cloud Storage (GCS) and fallback to S3 automatically.

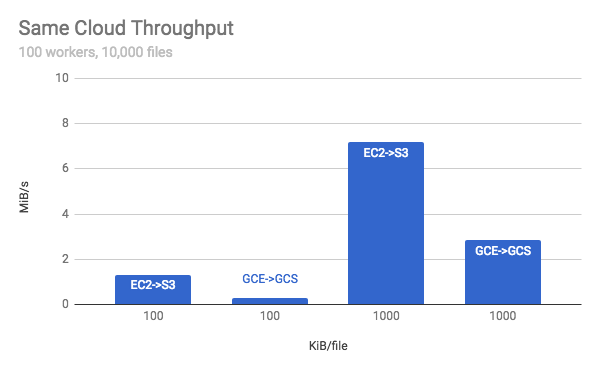

We first built a tool called cloud bench that would check the performance of uploads to different cloud storages. It showed us what we suspected: upload to a cloud storage was faster if it stayed in the same provider. We also confirmed that pricing was better if uploads stayed inside the same network.

We went through the different services that touched the data in the cloud provider, extracting simple Get/Put interfaces for that data and implementing concrete versions for Google, Amazon, and Rackspace. We then released the service, with the abstracted interface, that would use Rackspace — our current cloud provider. Then we started to test that service with the different implementations for the other clouds.

AWS and GCP offer more robust load balancers than what we were using. Rackspace is limited to around 10GB/s, which is a lot under normal operation, but not in the event of DDoS. Both Google and Amazon don’t place any limits, saying that the frontend load balancers will scale up as needed to support the traffic.

Data Replication

Netlify customers have deployed terabytes of data and they’re deploying more every day. Before the migration, all of this data was stored in a single service: Rackspace’s Cloudfiles. Our first challenge was to build a system able to replicate the millions of blob objects we stored and start replicating new data as it came in.

Our approach attached a bitmask to the object reference that indicated where it was replicated. We did this to keep down the bloat on the database as there are millions of entries and adding long strings to each would balloon the database size. It also meant that any service that needed to use that blob now knew from where it could load the data. This bitmask opened the way for intelligent prioritization in different services.

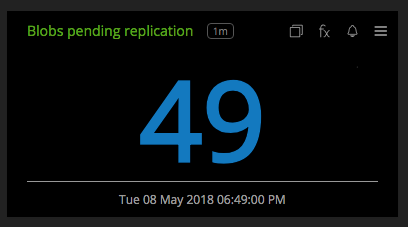

We built a Go service that would inspect an existing blob, figure out where it needed to push it to, actually push it, and record its progress. The service was able to act in both online replication and batch backfilling modes.

We fed a few million objects to the service for replication. After manually checking those blobs, we started two processes. One that would process newly-uploaded objects and one to backfill the existing objects.

We chose a passive replication strategy for the objects; the service would come through and clean up from time to time. A more active strategy, like a 3-phase commit, introduced risk into the upload phase. For instance, bugs or provider issues could slow or disable uploads completely.

It is also a simpler change in our system as it didn’t impact the request chain at all. We could iterate on the service with minimal risk to the primary flow. There is only a small fraction of objects that aren’t replicated in the event that we swap providers. Objects are available across providers and the system automatically handles that.

Recovery

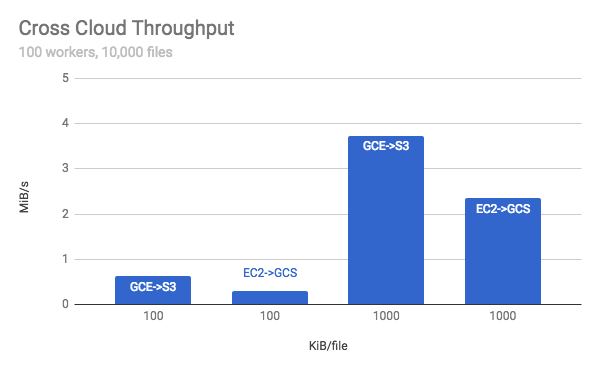

The system is flexible enough to handle recovering quickly; we’d take degraded performance over an outage any day. Traffic can be quickly redirected internally by updating service configurations. We can direct traffic to any of our clouds, including splitting traffic, in order to keep from dropping requests. Of course there are cost and performance considerations when doing this, especially when crossing cloud boundaries, but uptime is the priority.

Just the other day we had to configure a cross cloud setup. We detected a latency issue in our Google integration and manually intervened to swap reads from S3 while we investigated. Once we worked out the kinks with the integration we returned the configuration to its resting state, preferring the cloud the service was in.

Doing things manually is often too slow. We needed the system to be smarter, preferring to serve the request even if it would be slow. To accomplish this, we made it so that our services all had fallbacks for each provider. The service could look at the bitmask of the content it was serving and then try each of the providers by priority. If the node was in Google, it would prefer GCS, but in the event of an error it would automatically load that from S3 or Cloudfiles as appropriate.

Database considerations

As with most companies, our database sizes keep going up. In Rackspace we had to manually create LVMs and rehydrate the instance. Doing this caused one of our secondary nodes to be unavailable for around a day. We run five fully-replicated nodes spanning two providers, meaning it wasn’t an unsafe procedure, it was a unnecessary risk. Now in Google and Amazon, we can provision much larger disks, as well as do quick resizing of the attached disks. We don’t have to completely destroy the node, just suspend, resize, and start it.

One of our main worries in the migration was doing the database step down. We had a chicken and egg situation: either we move the origin traffic then the database master or vice versa. In either case we would increased the latency-per-query. We do around 1500 req/sec and if we introduce extra latency by spanning providers, we could put enough back pressure on the system to start dropping requests. It would only be a few minutes while traffic swapped over, but it was a definite risk. To compensate, we made sure that we were at a low point in traffic, that we had plenty of capacity to swap over, and that were quick about it. We ended up choosing to move the database master then origin traffic. Ultimately, it was ultimately not a concern. The query times jumped up but not enough to impact serving traffic.

Testing for a full migration

After we updated all of the services we could to be cloud agnostic, we started testing. Lots of it. We needed to test all the ways that people interact with the systems that touch a provider, like uploading assets and deploying sites. We tried to be exhaustive because we knew that the first cutover would be risky — it was picking everything up and shifting it. If we missed one hard-coded path it could have tanked the whole migration.

The driving question of the testing phase was, “How will we know when it isn’t working?” That drove us to create a document with all the outage scenarios we could come up with. We made sure we had the monitoring in place to detect errors, as well as code that should handle the event. Once we had a reasonable unit test suite, we spun up all the boxes and services in the request chain as if they were production. We started to run sample requests through those services to verify that nothing was being dropped and timings were acceptable. We found some gotchas and quickly iterated on fixing those.

Once confident that our staging area was working right, we started to send it a small trickle of production traffic. We carefully watched all the charts and monitored all the incoming requests possible, making sure that none of them were dropped or stalled. We did this in each provider — carefully verifying that the services were preferring the right providers, that response times were roughly the same as the actual production system, and that no service got backed up from increased latencies. Now it was just a matter of actually picking up the origin and migrating it to another cloud provider.

Actually pushing the button

Now that the whole platform team was confident that Netlify’s origin servers were sufficiently agnostic, we had to do the actual cutover. The steps to the task were:

- Spin up the new capacity in the secondary provider.

- Fail the database primary over to the new provider.

- Update the entries in our service discovery layer.

If successful, all the edge nodes in the CDN would automatically start to send traffic to the new nodes as the value rolls out. Each of the edge nodes would start to prioritize instances that are in the same provider and traffic would flow uninterrupted.

We chose a Sunday night to do the actual migration because that’s when Netlify sees its lowest traffic levels. The whole platform team got on a hangout, loaded up our dashboards, and prepared to aggressively monitor for errors or degraded performance that might result from the steps to come. Then we started pushing the buttons. We narrated each step, coordinating, and talking about any issues we saw. Thanks in large part to the planning and testing that went into the migration, the night was mostly spent chatting while the migration went off without a hitch.

As a result of the migration, we can now swap between different cloud providers without any user impact. This includes the databases, web servers, API servers, and object replication. We can easily move the entire brains of our service between Google, Amazon, and Rackspace in around 10 minutes with no service interruptions. Side note: Netflix’s world-class engineering team recently got failovers down from nearly an hour to less than 10 minutes. We’re going to work our tails off to beat their record.

What comes next?

We have tested that we can fail over our origins to the other providers as well, just not done the full failover. Going forward we are going to be adding more monitoring (as always on a platform team). We also set up a live standby in the other providers that we will be sending a trickle of real traffic to in order to make sure it is always ready. Then we are going to be taking steps to work to reduce the amount of time it takes for us to switch — our goal is under a minute — and remove any manual steps. As we refine the process and add more insights we think that we can reach that goal.

Every investment in our infrastructure introduces some level of risk and this project was fraught with it. I joined Netlify two years ago and we’ve talked about the importance of this project almost weekly since then. In that same time, it became increasingly clear that our current cloud provider could not offer us the quality of service we want to provide to our users. To me, this was a huge accomplishment and a great example of what a good team like ours can do. If you’re looking for a home on a platform team that’s doing exciting work, we’re hiring. Let’s have a chat or a coffee.