Service workers in the browser are getting a lot of attention lately, but what exactly are they?

What are Service Workers?

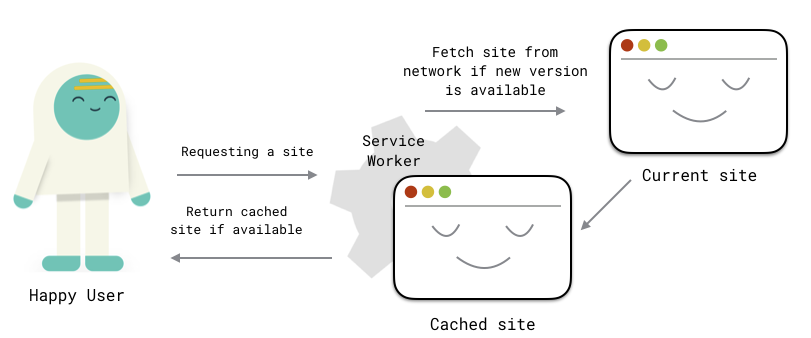

Service workers are proxies that sit between the web page and the network, providing cached versions of the site when no network connectivity is available. This is the foundation of Google’s Progressive Web App (PWA) standard that provides potential performance improvements by leveraging the cache for almost instant page loads. The service worker script runs in the background making the decision to serve network or cached content based on availability. The older form of browser caching, AppCache, was a more error-prone solution for offline-first ready applications. You can think of service workers as their successor.

The cache is not solely for offline. It also benefits the user during moments of slow or lowered connectivity. Rather than waiting endless seconds for the page to load, a previous cache is presented initially. Even high speed internet can be unpredictable, connectivity can drop intermittently throughout a session. Caching your site ensures there’s always a version ready to go despite the shortcomings of ISP or cell providers.

It is also important to note that, service worker scripts run on a separate thread in the browser from the pages they control. There are ways to communicate between workers and pages, but they execute in a separate scope (Thanks to the Making a service worker case study for that revelation). Service workers are not meant to and do not have the ability to manipulate the DOM directly.

Getting started

You can start using service workers by adding a few lines to your JavaScript file that registers a service worker. This code is usually written in your top level JavaScript file (i.e. index.js or app.js). I added a service worker to my project in case you just want to jump in the code. You can deploy a version of your own to Netlify.

Register a Service Worker

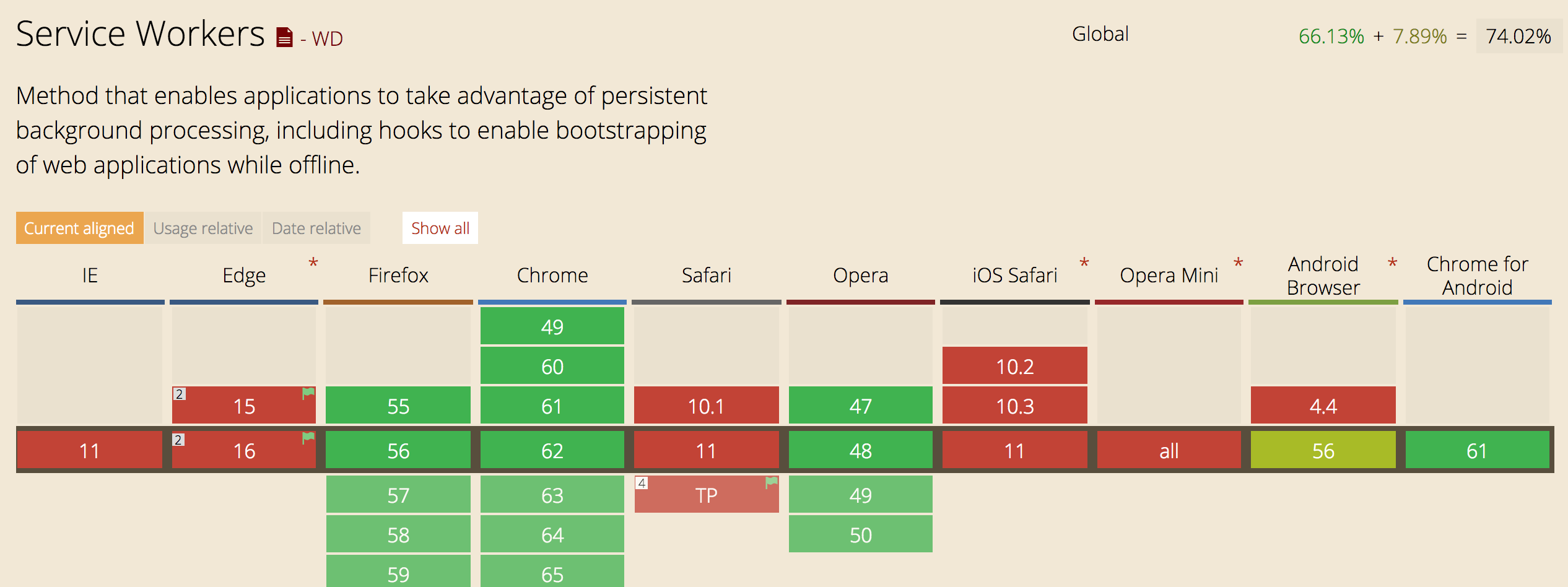

Services workers are still considered a “cutting edge” feature and not supported on all browsers. Only Chrome, Firefox, and Opera have full support for service workers and their browser caching.

To ensure your site will only attempt to register a service on a browser that has it enabled, you will need to wrap the registration code with a scope that checks to see if service workers exist in the browser navigator. I do this by checking if the browser’s navigator includes serviceWorker:

// app.js

if ('serviceWorker' in navigator) {

window.addEventListener('load', function() {

navigator.serviceWorker.register('/sw.js').then(function(registration) {

// Registration was successful

console.log('ServiceWorker registration successful with scope: ', registration.scope);

}, function(err) {

// registration failed :(

console.log('ServiceWorker registration failed: ', err);

});

});

}If all goes well with the service worker you’ll need to handle the browser caching by leveraging the common service worker lifecycle events.

Lifecycle

The service worker operates in through a predetermined event structure called the lifecycle. Understanding how you can manage each event and its response is the best path towards seamless caching and providing updates to your end users.

The service worker lifecycle includes 6 different event types:

- install

- activate

- fetch

- message

- sync

- push

In this post, I will only cover the first 3 events needs to provide an offline caching feature. I am registering a service worker using a file called, sw.js. This is the file where I set up my service worker. Inside this file I am leveraging, install, activate, and fetch.

// sw.js

const cacheName = "kaldiPWA-v1";

const filesToCache = ["index.html"];

self.addEventListener("install", function(event) {

// Perform install steps

console.log("[Servicework] Install");

event.waitUntil(

caches.open(cacheName).then(function(cache) {

console.log("[ServiceWorker] Caching app shell");

return cache.addAll(filesToCache);

})

);

});

self.addEventListener("activate", function(event) {

console.log("[Servicework] Activate");

event.waitUntil(

caches.keys().then(function(keyList) {

return Promise.all(keyList.map(function(key) {

if (key !== cacheName) {

console.log("[ServiceWorker] Removing old cache shell", key);

return caches.delete(key);

}

}));

})

);

});

self.addEventListener("fetch", (event) => {

console.log("[ServiceWorker] Fetch");

event.respondWith(

caches.match(event.request).then(function(response) {

return response || fetch(event.request);

})

);

});Install is the event that gets the party started. On this step, the service starts the caching and if content is cached successfully the service worker becomes installed. In my activation event, I am caching all files in my filesToCache array. If this step fails the service will not proceed to activate.

The activate event is the place where cache management happens. If the service worker installed successfully, this step is the activation button that makes that cache available for validation purposes.

Fetch will validate/invalidate the cache and leverages event.respondWith to do so. The response from the event returns a JavaScript Promise with all active caches. If the request is already in the cache, then cache is returned immediately. If the request is not cached, then service worker starts to fetch for a new cache.

Gotchas with Service Workers

There is a fair amount of advocacy for service workers, but there a few things to keep in mind. The first thing is that service workers require that the site is served over HTTPS.

Caching content and fetching messages in the background can be risky and open the door for man-in-the middle attacks. Chrome and Firefox recommend all traffic be served over HTTPS to prevent malicious attacks, which is why service workers will not work on unencrypted HTTP. If your site is not being served via HTTPS, you can set it up on Netlify with our free one click let’s encrypt support. Oh, and it’s free.

Make sure you have a cache invalidation strategy. My solution above only scratches the surface for what service workers can do, but Google’s sw-precahce is a service worker framework that provides invalidation out of the box. There are versions of sw-precache that have gulp, grunt, and webpack support so if you are using those build tools most of the work is done for you.

I recommend not running service workers in localhost environments. If you do so the same port will always run that same version of that site, regardless of what project you are viewing, since the local version of your site is not connected to the network. If you happened to do this, use the chrome://serviceworker-internals/ URL to unregister the service worker on localhost. For more information on how to circumvent service worker issues, check out the first 7 minutes of Alex Pope’s ServiceWorkers Outbreak: index-sw-9a4c43b4b47781ca619eaaf5ac1db.js JSConf EU 2017 talk.

Further reading and examples

If you are interested in hearing how Pinterest is using service workers at the next level, check out my introduction to service worker conversation with Zack Argyle on JAMstack Radio.

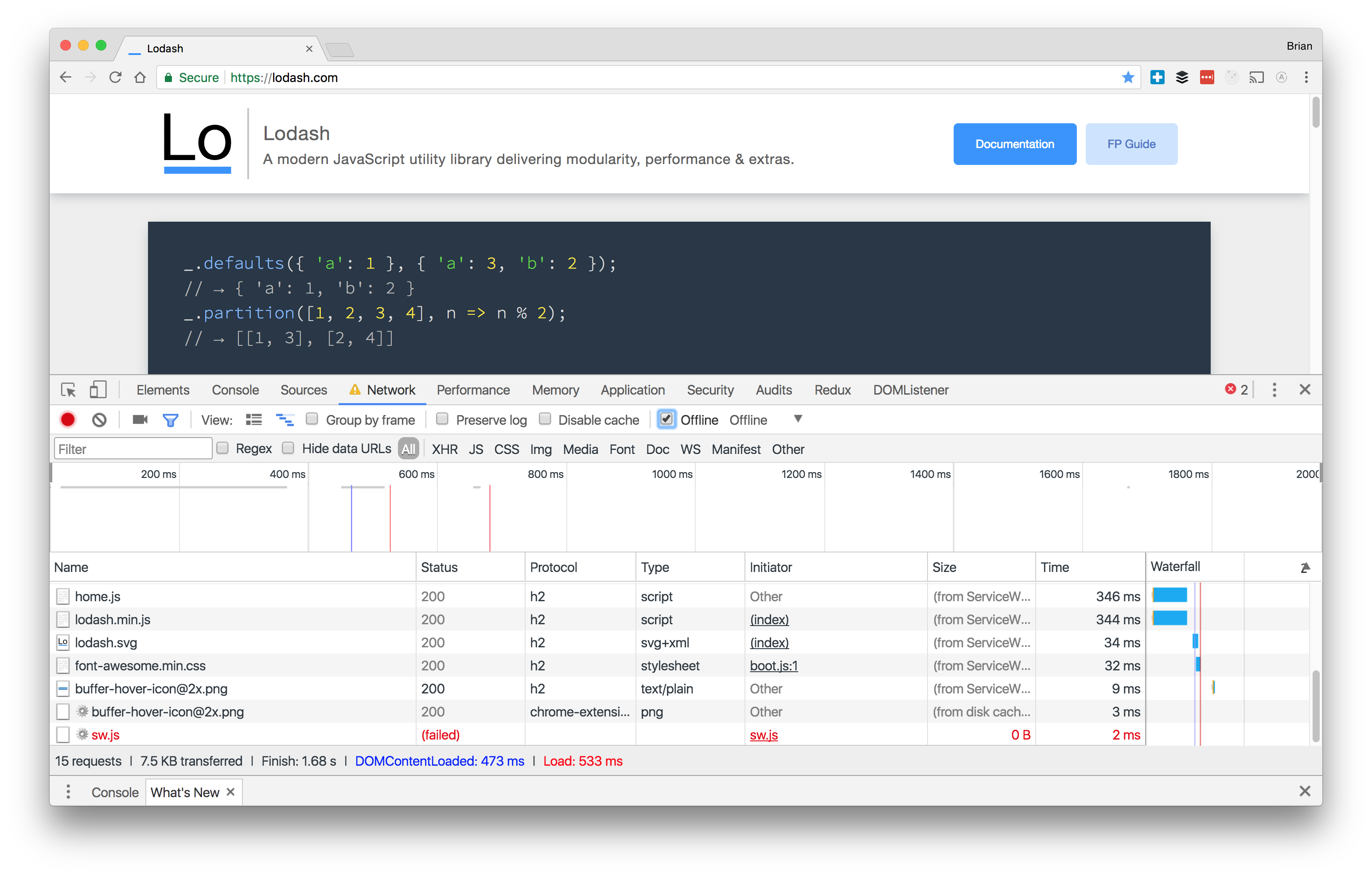

For a live example of a service worker in action, checkout lodash.com and click the offline checkbox (nested in the network tab of the dev tools) to check out their service worker live in action.

Their sw.js is open sourced and available to view as well.

There’s more to service workers than what we’ve covered here, like client-side load balancing for image assets and push notifications (and I’ll cover that in a future post). For now, check out other interesting use cases for service workers and Google’s Udacity course on service workers.