Last year I attended a NodeSF meetup where Francesca Guiducci spoke. Francesca has been working with GraphQL for years at scale, at companies like Trulia and Pinterest, and has been key to a lot of migration and development. In her talk, A GraphQL Guide for Backend Developers, she walks through a lot of very good, battle-tested advice. Since the event wasn’t captured, here’s a brief summary of her talk (taken with her explicit permission).

This post assumes some familiarity with GraphQL. If you’re brand new, the official docs are quite good, and Scott Moss has some great courses on Frontend Masters on it.

Does GraphQL fit into your architecture?

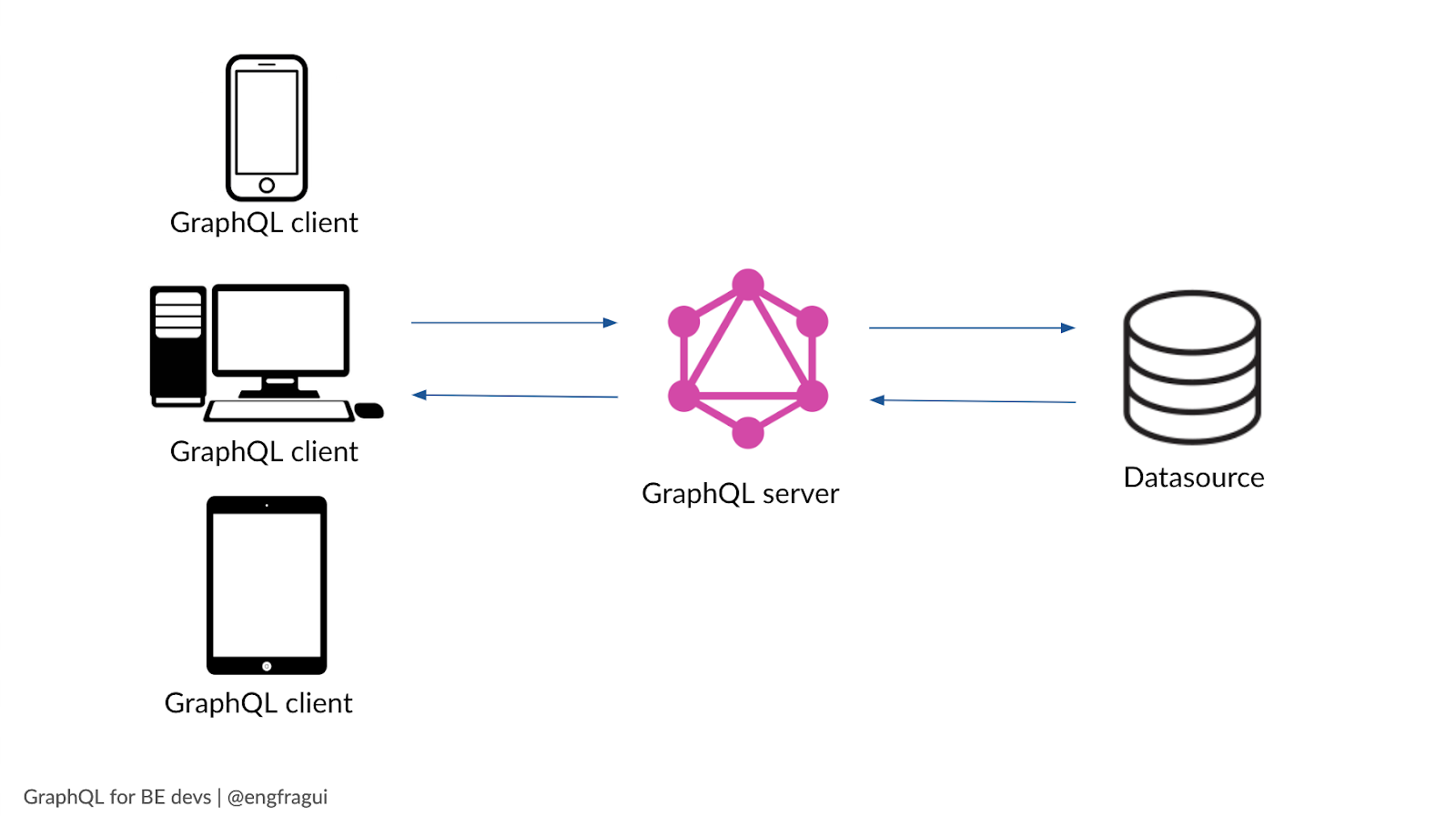

If you’re building a brand new application, starting from zero, putting a GraphQL server in front of a database will help create minimal architecture.

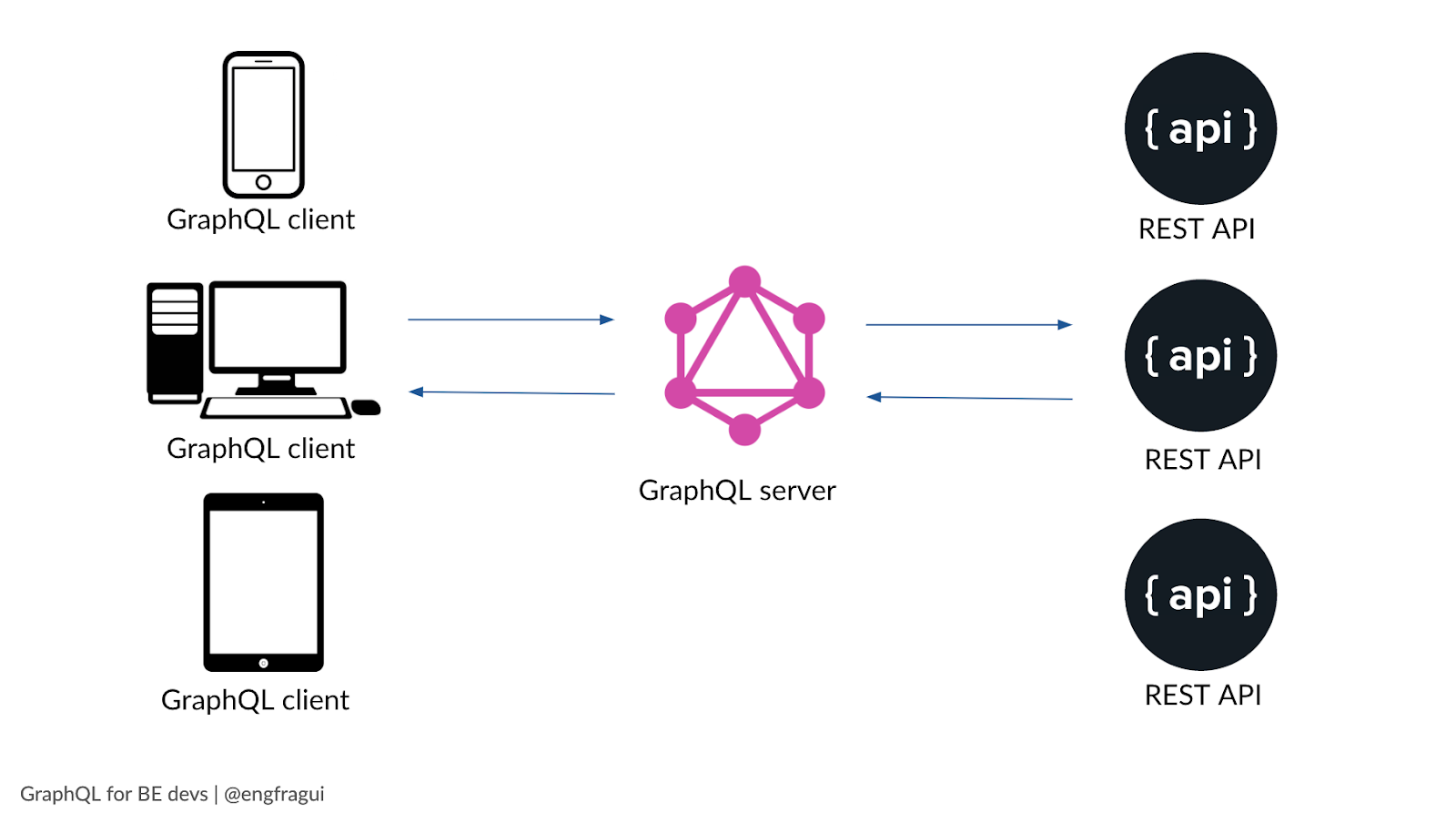

Similarly, GraphQL can be used as a light wrapper around existing APIs if your microservices are already built out.

These services can be REST APIs, but they don’t necessarily need to be. They can also be Thrift services or databases or a combination of all the above. (For more information on microservices, we have a write up that explains them).

Once you decide where you want to put GraphQL, it’s time to design the schema.

Involve others when designing the GraphQL schema

It’s crucial to include others in the design process. Though Francesca has done this exercise at scale, she stressed that this consideration is valid for both small and large teams.

Identify the people that are knowledgeable about the domain, people that work with the data you want to model, bring them in a room and brainstorm together, disagree with each other, get everyone’s thoughts out in the open. Specifically, she recommends disagreeing a bit, but not too much.

She cautions that you want to spend quite some time designing your schema. This is a very important phase, since the schema will become your source of truth, and will be a shared representation of the world that everyone will be referring to.

Start Thinking in Graphs

GraphQL is not about exposing methods, or creating endpoints, it is about the data and the connections among the different entities.

Technically, you can generate your GraphQL schema from your REST API schema using automated tools. However, Francesca doesn’t recommend this. There are a lot of benefits to carefully crafting and nesting your data in the way that makes more sense, not just how it’s represented in the database.

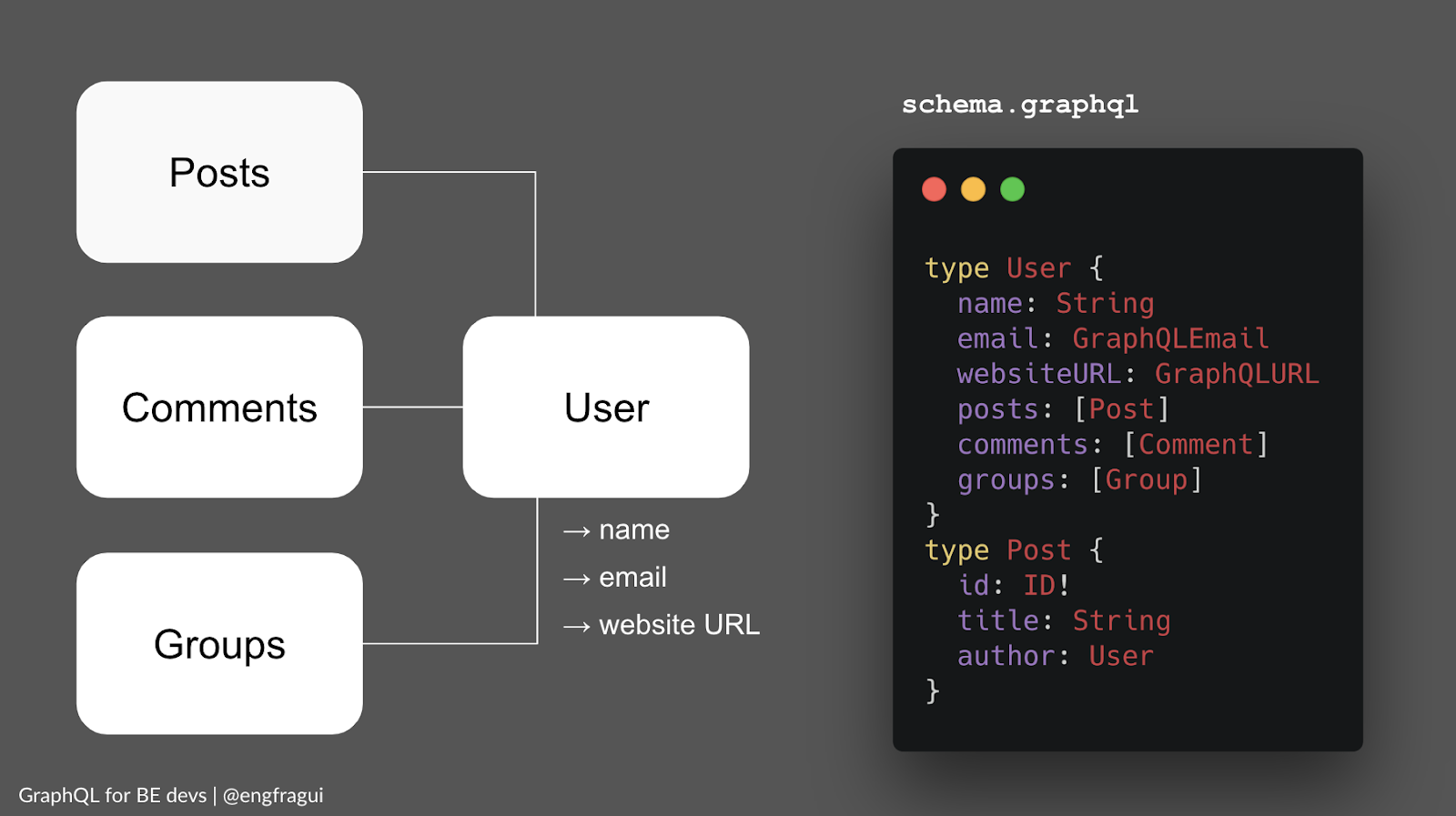

Let’s say we want to design the schema for a User type.

What information is relevant to a user? If we’re designing a user in the context of a blogging platform, details like name, email and website URL for one become relevant. Now what about relationships? A user can have posts, comments, be part of a group. Maybe the client is not currently interested in building a view where you see a combination of these entities. But if the relationship exists, it makes sense to model it in your GraphQL schema.

Based on the graph on the left, your schema might end up looking something like this:

As you can see from the image above, Not only does a user have many posts, but the type Post points to its author. This is what thinking in graphs means.

What else can you do to write a good schema?

Designing a schema that is easy to evolve

If you’ve designed REST APIs, you know that you can always rely on versioning if you need to introduce a breaking change.

However, GraphQL schemas change through evolution, not versions or breaking changes, so you need to try to keep your schema as “smart” as possible, forward-thinking so that it becomes easy to evolve.

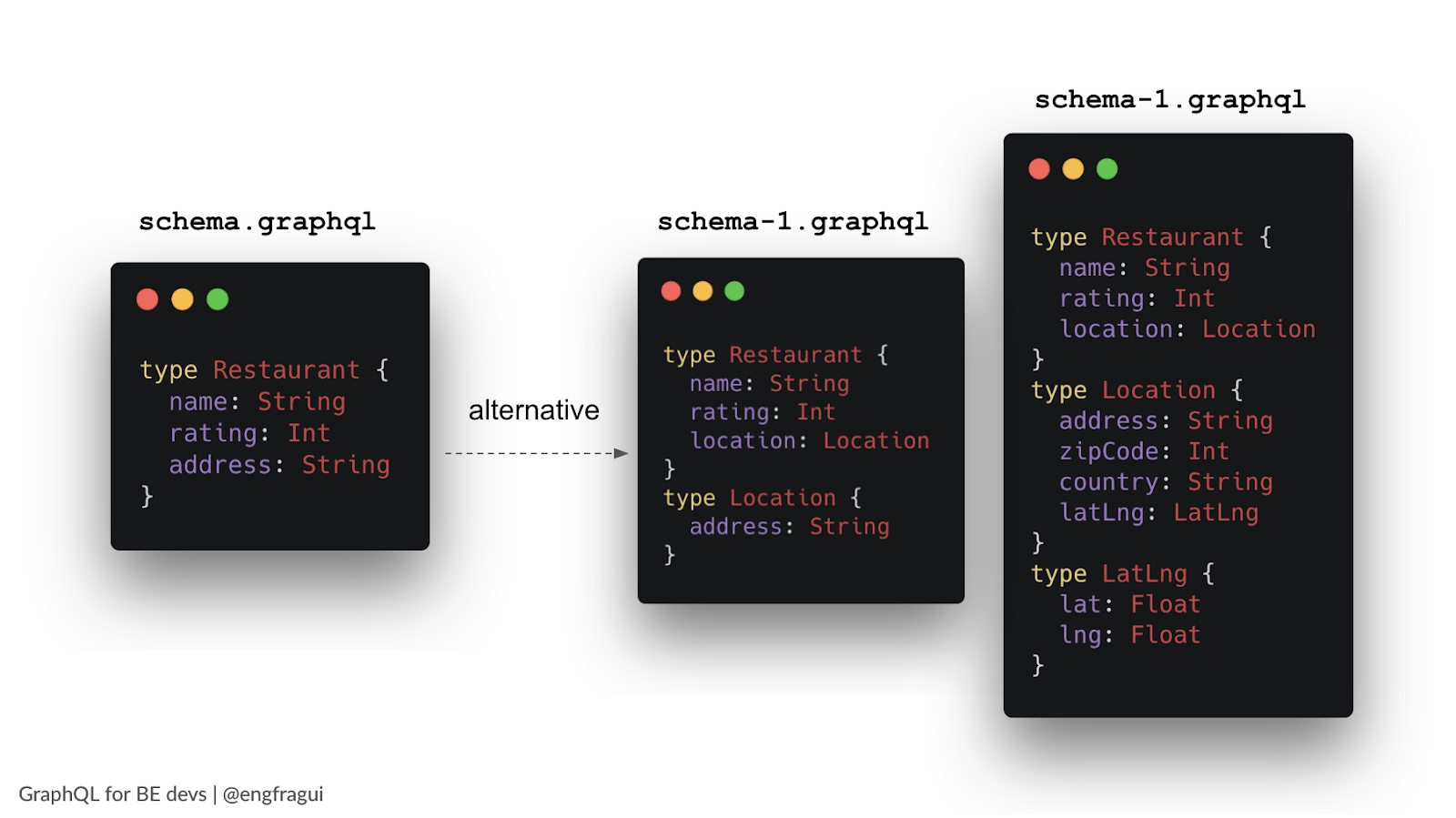

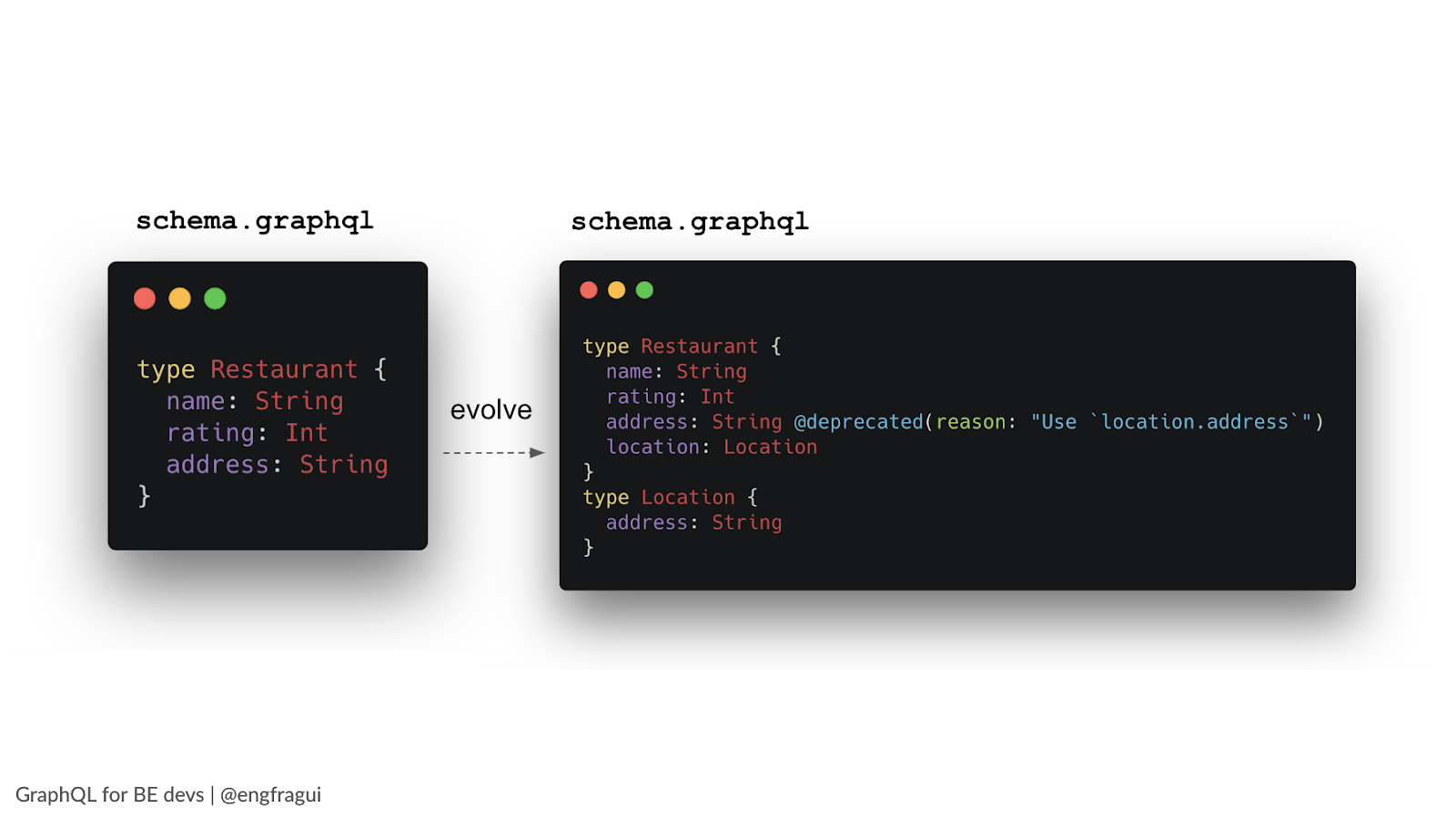

Say you’re designing a schema for a restaurant and you want to assign a few fields to the restaurant: name, rating, address. Simple enough.

However, it’s likely that you’ll need to expose other info related to location. In this case, what you can do is wrap the address in a location object. This will make it cleaner to add other info about the location like zipCode, country, latLng if you need instead of having them at the root level.

If you for some reason started with the initial schema (schema.graphql), don’t fret. There’s still a way to change the schema so that we get rid of address and move to location instead.

Enter the @deprecated directive. With this feature, The deprecated field will continue to function, (as long as you don’t remove the logic to retrieve that field from the backend.)

And when you know that there are no clients using that field, you can eventually remove the “address” field altogether. To understand when you can safely do that, you can monitor the GraphQL queries coming to your server: if no one is requesting a certain field then you can safely remove it. A tool that allows you to do this is Apollo Graph Manager, a cloud service for managing and validating your data graph.

Being intentional with GraphQL schema nullability

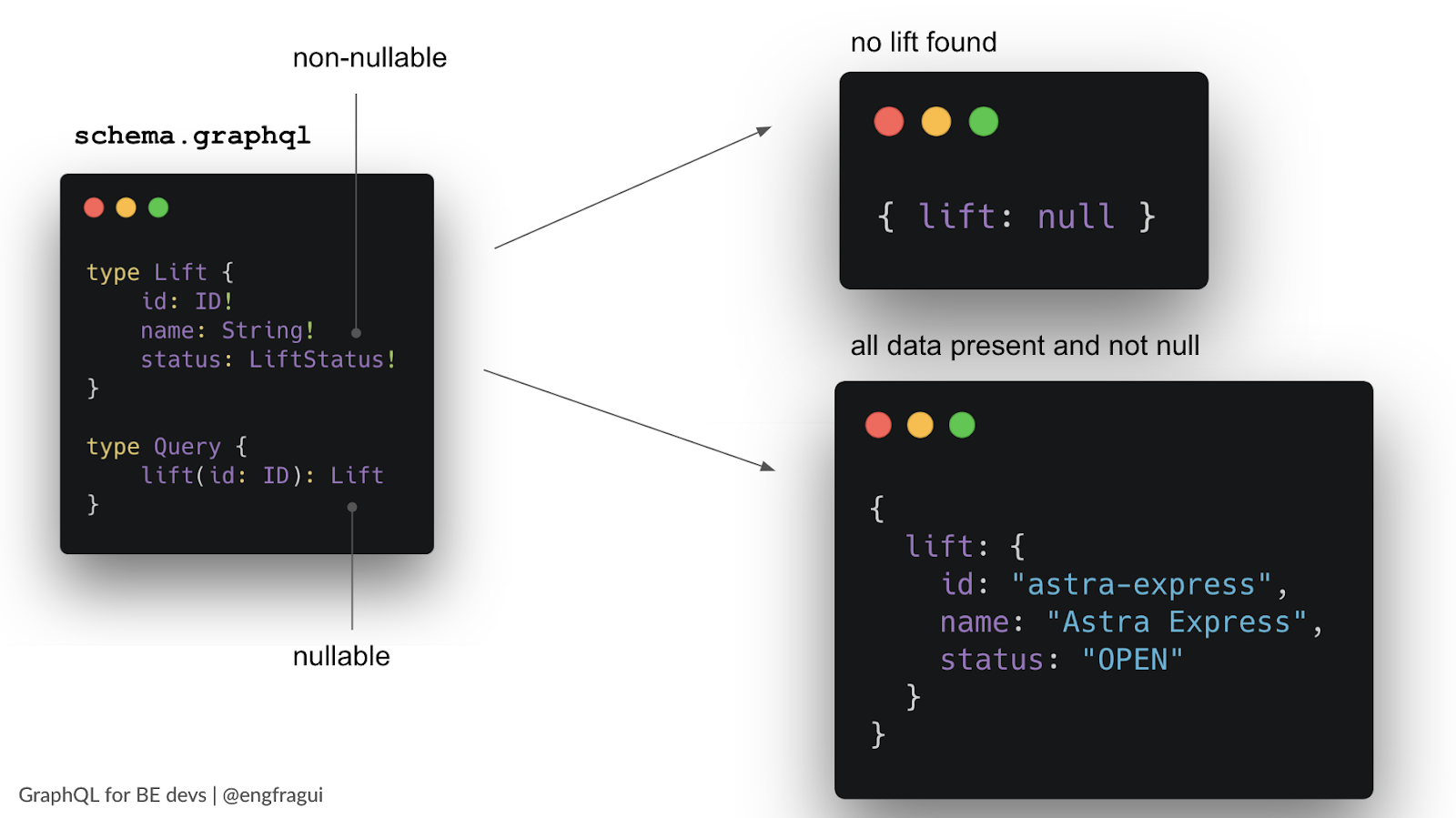

Something that usually gets overlooked when designing a GraphQL schema is “nullability”.

By default every field in GraphQL is “nullable”. This means that every field could be returned from server to client with the value null and still be part of a perfectly valid response. It also means that on the client there needs to be logic to check if the field is null, and actions need to be taken based on that. Note that if you need to do this for every field, this might prove to be a little cumbersome.

When we design the schema, it’s possible to come across fields that are always logically needed as part of a type. A typical example of this is an ID field. There’s a way to express that these fields will never come back as null so that the client logic can be simplified and we can further clarify the contract between client and server.

To define a field as non-nullable we can use an exclamation point after the field type. In this case we marked id, name and status as non-nullable, but we kept lift as nullable.

This means that lift can be null, so it’s possible that it will return as “null” from the server, for example if the lift is not found.

On the other hand,if the lift object is present in the response, we know for sure that all the fields will be populated. Based on how we design this schema, the client knows for sure that a lift cannot have just id and name but no status.

Implement pagination if it might be useful

GraphQL can return lists as well.Unfortunately, the GraphQL spec does not provide a structure for pagination, meaning that the implementation is up to you.

There are a number of ways in which we can design pagination:

- The simplest way is to expose first and offset parameters. If a client makes this request, it simply means “give me the first 2 friends starting from friend n.4”

friends(first:2, offset:4)- You can also choose to expose “first” and “after”. This query for example means “give me the first two friends after a specific friendId”, which typically is the last friendId that to the client in the previous response

friends(first:2, after:$friendId)- Another way is using cursors, which is a more opaque way to paginate results

friends(first:2, after:$cursor)Implementing pagination is important to ensure we don’t fall into the pattern of returning a large list of items to our clients, as it limits what is returned.

Challenges

- We mentioned this before: versioning is frowned upon. I would consider it a challenge because we’re so used to it and it’s difficult to set it aside. However, alternatively you can keep your schema easy to evolve and mark fields as deprecated if you need to.

- We also already mentioned that there’s no standard way to implement pagination, so it’s up to you to decide how to implement it based on what makes the most sense in your use case.

- Performance. GraphQL is designed in a way that allows you to write clean code. However, if your implementation is naive, your code could repeatedly load data from your database: this is called the N+1 problem. For example, when you want to fetch a list of authors and each of their respective articles, a naive implementation will make one query for a list of n authors but then it would make n queries to get articles for each author! There are tools to batch queries and avoid the problem. Using Facebook’s DataLoaders, multiple requests for data are collected over a short period of time and then dispatched in a single request to an underlying database or microservice.

- Possible malicious queries: Having a graph interface could allow clients to send queries that are malicious (example: author – posts – authors – etc). To prevent this issue you could have a set of whitelisted queries, which would be the only queries allowed to your server. The downside is that it goes against GraphQL’s flexibility, another alternative could be setting a timeout, or limiting the query depth.

- Testing needs to cover a large surface area, so you really need to have end-to-end tests. The good news is that since the schema has types, it makes this a little bit easier when testing.

- You can’t rely on HTTP error codes: We’re quite used to relying on HTTP error codes, but GraphQL doesn’t work that way and instead, it communicates errors with error messages. We need to be careful and thoughtful when designing these error messages, so they can be as useful as possible.

Francesca has a lot of experience using GraphQL in practice, these pieces of advice and challenges outlined above are useful to set a project on the right track.