The code review is a critical part of life as a professional developer: in most engineering organizations, no code gets checked in without at least a once-over from another engineer. This has many benefits for enforcing code standards; however, we can run into communication issues if we don’t establish standards for the code reviews themselves.

To solve this, Netlify’s UX team developed shared terminology for code reviews that we call the Feedback Ladder! It has worked very well for Netlify and we share it in the hope that it helps your team.

The Problem

Code reviews catch everything systems cannot. We can run Prettier and lint rules and automated unit/integration/end-to-end tests all we like. But people still have to check that tests test the right things, that code conforms to agreed-upon standards, that comments and naming and code organization and architectural choices can be maintained by others.

However, there isn’t a binary divide between good code that can be merged and bad code that must be changed. There are tradeoffs between ideal solutions and speed of shipping: Perfect is the enemy of good. Code review feedback isn’t all created equal either – sometimes you could just be pointing out a slight optimization, sometimes you could be ringing the alarm bells on a blocker that deserves immediate attention!

Last but not least, code review is still a form of asynchronous communication, so a lot of context (like body language and the opportunity for back-and-forth) is lost. This is especially important to us as a majority remote company, so we wanted a way to add some nuance to our feedback.

Many developers indicate the priority level of their feedback by noting if it is a “nit”. A “nit” is like a “nitpick” – you’re voluntarily indicating the low severity of the issue discussed. However there is still a lot of room for interpretation – some “nits” are still code standards issues, and not every piece of feedback without a “nit” is a high priority blocker.

The Solution

The system Leslie eventually landed on was the idea of the Feedback Ladder. When giving feedback, it helps for the team to use shared terminology to better understand where the feedback fits into the larger picture. This is especially necessary in the context of our work, where we aim to ship fast, iterate often, and squash blockers as quickly as possible.

In an effort to make the levels of the feedback ladder easier to remember and use, Kristen came up with metaphorical names to describe each step. The idea is that you’re living in a house that’s still being built. Each of the “inconveniences” we’ve listed (mountain, boulder, pebble, sand, dust) has a different level of impact on your day-to-day life in the house. For example, you may notice dust on the floor, but it doesn’t impede your ability to live your life; on the other hand, a boulder blocking the door would quite literally be a blocker.

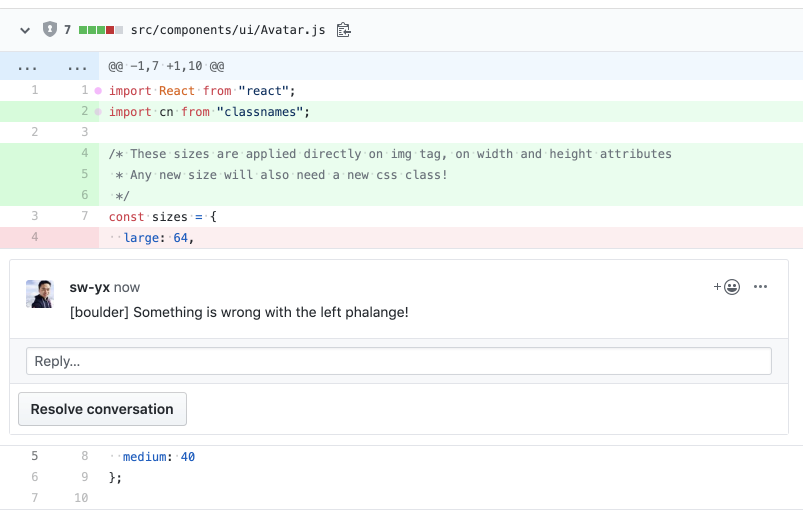

We prefix each piece of feedback with the name in square brackets, like so:

The way we give and receive feedback for each step on the ladder should scale appropriately according to its severity.

⛰ Mountain / Blocking and requires immediate action

This mountain has torn the roof off of your house. There’s no room for you inside, you gotta take care of that right away before doing anything else!

This feedback blocks all related work, and requires immediate action. This type of feedback should never be given in direct message or private conversation.

Example: A developer is working on an issue and discovers more about the problem domain that was not previously known, realizing that the issue itself needs to be taken back to the drawing board because it is not feasible, needs to be broken up, or the solution doesn’t actually address the intended user stories.

🧗♀️ Boulder / Blocking

This boulder is blocking the door, people can’t get in and you can’t get out. You gotta get it out of there. But you can take care of some other stuff first, like finishing installing the lights in the kitchen.

This feedback should block the work from moving forward or being approved, but it does not necessarily require immediate action from the team.

Example: A feature has been implemented and tagged for review. When testing the Deploy Preview, a reviewer notices that the wrong API endpoint is being used and the data displayed in the frontend is incorrect.

⚪️ Pebble / Non-blocking but requires future action

This pebble is super frustrating when you encounter it on the floor, but it doesn’t get in your way that often so you can deal with it later when you have time.

This feedback should not block the work from moving forward or being approved, but it does require future action from the team. This generally means the feedback is not required for the MVP or initial draft of this work, but should be addressed at some point.

Example: During a Design review, a designer says they would like to change the background color of a status badge to help make the status more clear.

⏳ Sand / Non-blocking but requires future consideration

It’s a little annoying to have sand in your house; you should consider later if it’s worth cleaning up. But maybe you just end up pointing out to folks that your house is at the beach so it’s always gonna be a little sandy no matter what and you’re willing to live with that since you get to be at the beach!

This feedback should not block the work from moving forward or being approved. The project lead or owner should consider the feedback and implement it if there is at least one other team member who concurs.

Example: During code review, a team member leaves feedback about refactoring for readability. A very common example of [sand] feedback on the frontend team is code style or approach (not user-facing).

🌫 Dust / Non-blocking, “take it or leave it”

Some people may notice the dust and think it’s worth cleaning up, others won’t mind it at all.

This feedback should not block the work from moving forward or being approved. The project lead or owner should consider the feedback and implement it if they deem it useful.

Example: During code review, a team member suggests a different name for a new variable.

One more tip: The Ground Floor

We have found our Feedback Ladder system very helpful in concisely encoding severity of feedback, and think it will be helpful in other engineering teams too. You may wish to add or remove rungs when you implement this in your teams, and if you have any interesting variations on this idea, we’d love to hear them too!

One final tip for asynchronous code reviews: Roundtrips (from teammate to reviewer back to teammate) are expensive, costing up to two working days of a sprint each time. One great way to minimize the number of roundtrips is to preemptively review your own code, adding comments that are only meant to be read at review-time. (Of course, if the comment makes sense to future readers, consider adding the comment in the actual committed code itself!)

This lets you leverage your knowledge of your teammates and indicates that you are considerate of the concerns they would typically raise. This increases team trust and shipping velocity. As a pre-emptive measure before you even step on to the Feedback Ladder, you could consider this the “Ground Floor” of code reviews!